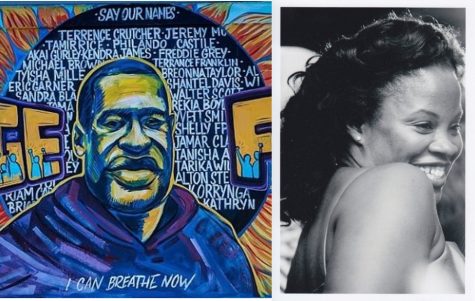

(l-r): George Floyd BLM mural painted by Greta McLain, Xena Goldman and Cadex Herrera; Nkoyen Ekpoudom

May 2020 (and let’s be honest the entire year) will be seared into my memory for the rest of my life. On May 25th, bystander video captured the final 8 minutes and 46 seconds of 46-year-old George Floyd’s life. On May 26th (having not yet seen the video of George Floyd’s murder), I made a post on social media celebrating my older sister Nkoyen Ekpoudom’s 45th birthday. While the entire world now knows of George Floyd, far fewer people had the pleasure and joy of knowing my sister. And only in the last few days have I learned how closely these two lives could have intersected, but never did. What do my sister and George Floyd have in common other than being black and similar in age? Both are dead. Both of their deaths were preventable. And both struggled to say these words in their final moments. “I. Can’t. Breathe.”

My Nigerian parents came to the United States in the 1960s to pursue their higher education. The pursuit of that education took them to colleges and universities in Arkansas, Ohio (where my mother completed her Master’s degree at Ohio State), Minnesota (where my father completed his MBA and where my oldest sister was born in Mankato, an hour and a half drive from where George Floyd died) and Nebraska (where my father earned his PhD in Economics at the University of Nebraska).

Like George Floyd, my sister Nkoyen was also born in North Carolina, he in Fayetteville, and she in Greensboro, where my family moved for my father’s first teaching position upon completing his PhD at the historically black North Carolina A&T State University. As was always their plan, my parents subsequently moved back to Nigeria raise their growing family. My brother and I were born in Nigeria. Due to political instability within Nigeria in the 1980s, my parents determined the best opportunities for their children would be back in the U.S. and we moved as a family. Our first stop? George Floyd’s birthplace of Fayetteville, NC, where my father became a professor at the historically black Fayetteville State University. My first years of life in America were spent in the same place where George Floyd spent his.

My family ultimately moved to and settled down in one of the most historic places in American history, Yorktown, Virginia, best known as the site where General Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington (he and I coincidentally share the same birthday of February 22nd), effectively ending the American Revolutionary War. Yorktown is also just about a 30-minute drive from where 401 years ago this August, in 1619, the first enslaved Africans arrived at Point Comfort in modern day Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, aboard the English privateer ship the White Lion. My father spent the rest of his academic career as a professor of finance and economics at historically black Hampton University.

My black family came to this country voluntarily from Africa in a plane. The first black individuals to which many of today’s African American families trace their roots came to this country involuntarily from Africa in ships and in chains. There is privilege in that.

I give this context because it can often be simple to paint the black American experience with the same broad brushstrokes. While I recognize that George Floyd and Nkoyen’s lives shared many similarities, there are fundamental differences in their lives that are rooted in their distinctly different experiences. The legacy of systemic racism on which this nation is built is felt and internalized differently by those who have lived multiple generations under this system versus those like my family who voluntarily chose to come here to seek opportunities.

But that doesn’t mean they were immune. Although they rarely spoke of it, my parents faced intense racism and xenophobia during their educational journey. Because of that, it was extremely important to them to raise their children in a place with some semblance of racial diversity, and most importantly because we were not wealthy, a strong public education system. The ability to make that choice made all the difference in the subsequent future opportunities that opened to Nkoyen, my brother, and me who all graduated from Tabb High School (go Tigers!). My oldest sister was already in college (at my mom’s alma mater Ohio State).

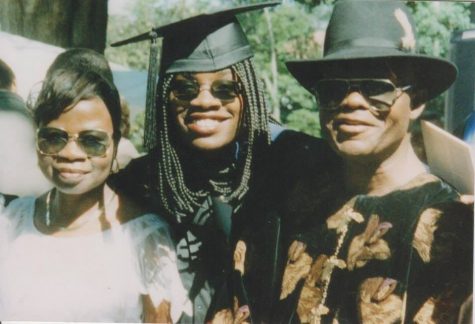

Nkoyen with our parents on her graduation day from Emory University in 1996.

Nkoyen went on to college at one of the nation’s top universities, Emory University. She then embarked on a professional career that ultimately led her to working for one of the largest Fortune 500 companies in the world. Towards the end of 2008 she had a full circle moment when she was promoted to be relocated to Africa to help the company grow their business on the continent. She was beyond excited and while I was excited for her, I was also more than a little sad that my sister would be moving so far away.

I got to share in her excitement when we both traveled together to her future home in Johannesburg that February 2009, I to be a bridesmaid in a dear college friend’s wedding, and she to meet her new team. We returned from the trip separately, I back to life in business school in Philadelphia, and she back to wrap up her final few weeks in the New York office.

That trip was the last time I saw my sister alive. Nkoyen died on March 3, 2009 (coincidentally on the same day when, 18 years earlier, Rodney King’s violent beating by LAPD was captured by a bystander on video) walking home from work on the streets of lower Manhattan. She died of a pulmonary embolism caused by a deep vein thrombosis, i.e., a blood clot traveled from her leg to her lungs and heart leading to cardiac arrest. In other words, she, too, slowly, and painfully suffocated to death.

How do I know what my sister’s last words were? Once again via a bystander. In this case, the bystander was a wonderful good Samaritan woman who saw the commotion as people gathered around my sister where she had collapsed and intervened to stop and stay by my sister’s side and try to help her in those final moments. She told me what those moments were like, including how Nkoyen gasped for breath and fought with everything she had to stay alive. I remain thankful to her to this day for the kindness and compassion she showed my sister and for being there to comfort her when I could not. It was even more devastating because it was the third family member’s death for which I had not been present. My father died in 2004, and my mother died in 2007. Both were living back in Nigeria.

I couldn’t let my sister’s death go. I was haunted by it and replayed those final weeks over and over in my head. I found an email I wrote just a few months later in June 2009:

“As the weeks have passed and I’ve learned more about the cause of her death, I’ve become more and more upset because I think it was preventable. Because she was so young, an autopsy was automatically performed by the medical examiner’s office. I recently received the final cause of death and it was stated as deep vein thrombosis in her left leg (i.e. a blood clot) which moved from her leg to her lungs and heart. The result was delayed because they ran genetic tests and other things to see if any other complications may have caused it. But as I suspected, there was nothing wrong with her.”

Some will say accidents happen to good people. But is it really an accident when someone who is not a hypochondriac visits 4 doctors in the span of 3 weeks complaining about the same issue as my sister did? How again did I know this? I didn’t have to guess. My sister was carrying her medical records in her bag when she collapsed. I was not yet aware of the data of the history of bias that exists in the medical profession that consistently discounts and dismisses black people’s pain. I didn’t yet know things like the astoundingly high and disproportionate statistics around things like maternal mortality rates of black new mothers. Even after the data was recently standardized. I didn’t know that these rates persist across socioeconomic classes amongst black women. Look no further than Serena Williams, who almost died from DVT/PE not once, but TWICE, once before she was pregnant at the height of her athletic fitness, and once after she gave birth. It seems neither all the education, nor insurance, nor money in the world helps when it comes to black women. Worst of all? March is National DVT Awareness Month.

I must admit when the outcry first happened and wave of protests began, I was initially confused as to why George Floyd’s death elicited such a different and immediate response. I realize now that this is where my sister’s story and his converge. We are in the midst of a global pandemic, one that the data shows is once again disproportionately killing black people in America. Why? According to the CDC:

- Where we live, learn, work, and play affects our health.

- The conditions in which people live, learn, work, and play contribute to their health. These conditions, over time, lead to different levels of health risks, needs, and outcomes among some people in certain racial and ethnic minority groups.

So because the majority of Americans were almost uniformly sharing the same experience of spending more time at home, we as a nation were home to witness the graphic events that led to George Floyd’s death within the span of a few hours to a couple of days after it happened. The rage over the blatant inequity in George Floyd’s death, coupled with the rage over the blatant inequity in the disproportionate representation of deaths among black people from the corona virus, lit a fire within this country that weeks later is still raging. We cannot unsee what we have seen.

The circumstances surrounding George Floyd’s death, my sister’s death, and the death of so many black Americans during this pandemic are not a coincidence. They are due to the systemic racism and unequal treatment that exists within the justice and healthcare systems in this country.

Black lives matter and we seek in 2020 the true equality with which our Constitution says all men were supposedly created. We can do better. We MUST do better.

I channel my sadness towards my purpose of driving economic justice for women through my work at GingerBread Capital investing in female founded and co-founded businesses. When I see companies in our portfolio like Iman Abuzeid’s Incredible Health, which helps hospitals more quickly and effectively hire the often most unsung heroes (nurses), or Lisa Skeete Tatum’s Landit, which helps companies invest in and develop its leaders, high potentials and yet to be undiscovered talent, or Jean Brownhill’s Sweeten which can help local communities unfortunately impacted by looting rebuild, I feel hopeful that my sister’s legacy lives on through my work.

The notion of trying to dismantle systemic racism seems daunting and overwhelming because it is. To achieve the changes we want to see in society, each of us must first be the change agents we wish to see in the spheres we can influence as individuals.

Most police officers are good. Most doctors are compassionate and competent. But it only takes a few bad actors who are not held accountable to erode trust in these systems when we need them the most. If you work in environments where you see bad actors amongst your teams, take the NYC transit saying of “If you see something, say something” one step further and actively DO something to try to stop it. If we first focus on our own homes, workplaces and within our communities, I believe our individual efforts will make this moment a movement.

![]()

Watch this moving video tribute to Nkoyen Ekpoudom.

This essay was originally posted on June 1, 2020.